The Tragedy That Paved the Way for Algerian Independence

On 8 May 1945, French massacres in northeastern Algeria radicalized an entire generation

Along with 1 November 1954, which marked the start of Algeria’s war of liberation, 8 May 1945 is the most powerful date, both symbolically and historically, in twentieth-century Algerian history. As a symbol of the brutality and repression of the French colonial order on the one hand, and of Algerian martyrdom and sacrifice on the other, 8 May marked the moment when the door definitely closed on political compromise. It consecrated the refusal of any dialogue between the colonial system and the colonized world, fostering a major rupture in the history of Algeria that transformed the nationalist currents politically, generationally, and psychologically, and accelerating the move towards armed struggle.

What exactly transpired on 8 May 1945? While Europe was celebrating the Allied victory over Nazi Germany, thousands of Algerians were killed during the repression of demonstrations in different regions of the country, mainly in the northeastern cities of Sétif and Guelma. According to Algerian martyrology, 45,000 died. French historians claim the figure was around 15,000 Algerians, compared to roughly 100 French victims. It should also be remembered that this happened during peacetime — there was no war in Algeria — and that the victims were civilians.

One week prior to the massacre, the French had already broken up demonstrations organized to mark 1 May, resulting in deaths. Protest demonstrations were to be organized the following Sunday, 8 May. This time, the level of repression was unprecedented, and included the participation of the French army, police, and Pied-Noir settlers organized into militias. Surviving images of the massacre depict corpses discarded in limekilns in Guelma, victims thrown off cliffs in Kherrata, and manhunts organized in the “Arab neighbourhoods” of Sétif. Numerous writings have been devoted to the events, the most complete of which is Le 8 mai 1945 en Algérie by historian Redouane Aïnad Tabet.

The events of 8 May came as a huge shock to the Algerian population, and caused a real trauma for the political elites, both those already leading nationalist parties and those who were still forming. Until then, and despite their more or less radical opposition to the colonial order, Algeria’s nationalist leaders had confined themselves to strictly legalist and peaceful action. The brutality of the repression, and the savagery of the administration and various apparatuses at the service of the colonial system, both shocked them and pushed them to consider abandoning their legalist framework.

Furthermore, the repression put a brutal end to the ferment that had surrounded the creation of the Friends of the Manifesto and Liberty (AML), a movement that rallied the various pro-independence currents around a document transmitted to the American administration calling for Algerian self-determination following the American landing in Algeria in 1942.

Baptized by Fire

A whole generation of Algerian political leaders who would go on to launch the war of liberation in 1954 underwent their initial politicization in the AML, before being brutally brought back to reality by the massacre. These figures included Larbi Ben M’Hidi, Hocine Aït-Ahmed, Mourad Didouche, Rabah Bitat, Lakhadar Ben Tobbal, Abelhafidh Boussouf, and others who were not yet 20 years old, or had barely passed that age by the end of World War II.

A different group of future independence leaders was impacted by the massacre even more heavily: those who had been mobilized to fight in the ranks of the French army against Nazi Germany in World War II, and who, once demobilized, were confronted by what the French had done to their compatriots back home in Algeria. Among them were Ahmed Ben Bella, Mostéfa Ben Boulaïd, Krim Belkacem, and many others who were only slightly older.

This generation was thus taking its first political steps when it was violently confronted with the massacres in Sétif and Guelma. The experience mapped out their destiny. They resolved to change tactics in two essential aspects: to put the armed struggle at the heart of the national project, and to devote a sort of cult to the organization — the famous nidham (“order”), a word that has survived through the ages and is still in use today to designate a system or model of organization. Belonging to the nidham and putting oneself at its service became the supreme, indeed almost sacred value.

This model of organization constitutes the counter-example of what 8 May 1945 was: meticulous organization and discipline against improvisation, the cult of secrecy against spectacular action, the setting up of structures and networks to compensate for the weakness of spontaneous activity. This spirit and method are powerfully reflected in the first volume of Lakhdar Ben Tobbal’s memoirs published in 2021, a book that poignantly describes the political and psychological climate that prevailed before 8 May and the consequences of this event on the future evolution of Algeria.

Indeed, one can draw a parallel between the events of 1945 in Algeria and the 1905 and 1917 revolutions in Russia: a sort of impromptu rehearsal without any real preparation, claiming many victims and destruction, but after which participants drew lessons to ensure the success of a more thoughtful, more elaborate, better-organized operation. For 8 May was studied and dissected within the structures of the Algerian People’s Party (PPA), which was dissolved after the massacres and reappeared under the name Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Freedoms (MTLD).

These reflections flowed into an exceptional report presented by Hocine Aït-Ahmed to the central committee of the MTLD in 1948. The document, the result of collective deliberations, is one of the most elaborate attempts at theorizing guerrilla warfare in the late-colonial period. Two years later, the process led to the creation of the Special Organization, the OS, a secret structure that would serve as the matrix through which the National Liberation Front and the National Liberation Army (FLN–ALN) would be created in 1954, which in turn erected the Algerian state in 1958 and all the institutions that would follow.

A Contested Legacy

The main lessons of 8 May 1945 were vital for the success of 1 November 1954. The cult of secrecy, discipline, organization, the establishment of a strict hierarchy, the creation of networks, and, above all, the imposition of one’s own agenda rather than reacting to conjunctures or events — all of this was the opposite of the spontaneity and improvisation of 8 May 1945, ensuring that the preparation and launching of a movement as important as the war of liberation was decided in a totally autonomous manner, and was not detected by the French security services. This allows us to affirm that 8 May 1945 was not a dress rehearsal for 1 November, but rather a counter-model, an experience from which lessons had to be learned.

Moreover, an anniversary so laden with symbolism was naturally destined to become consensual. It is claimed by all political currents in Algeria, from liberals to Islamists and Communists and, of course, historical nationalists. It occupies a place of choice in both the official as well as popular martyrologies.

There are, of course, some rare criticisms of the official celebration of the event, with the government accused of exploiting history to reinforce its own standing. But as for 1 November, the tendency is rather the opposite: the government and opposition are in competition to appropriate the event, and sometimes engage in a kind of one-upmanship to claim it.

Abed Charef is an Algerian journalist, writer, and founder of El-Khabar, one of Algeria’s most widely read newspapers.

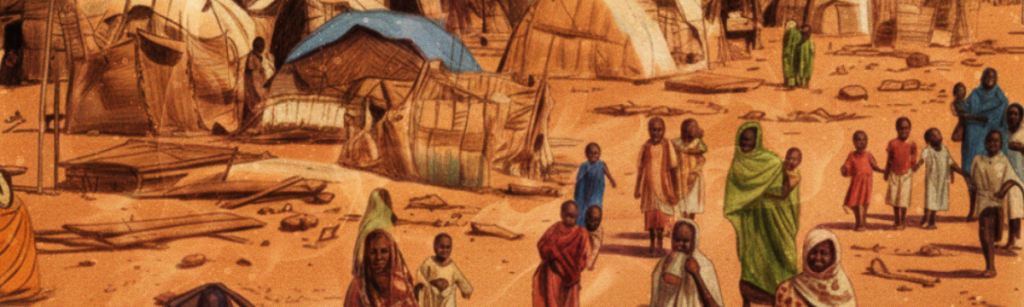

Photo: A rally organized by the Algerian People’s Party in the early 1940s (Wikimedia Commons/Author unknown)

The content of this text does not necessarily reflect the position of RLS