A Palestinian State in North Sinai?

A Palestinian State in North Sinai?

Mass displacements in Palestine, population management in Egypt

Since the beginning of the war between Israel and Hamas, prominent voices in Israel have openly called for the complete destruction of Gaza and the forced expulsion of its population to North Sinai, the strip of land belonging to Egypt on Gaza’s western border. Current and former Israeli officials bluntly advocate for a second Nakba, the Arabic word for “catastrophe” that Palestinians use to denote their mass displacement in 1948. Indeed, such calls began immediately after Hamas’ unprecedented attack on 7 October 2023. Hamas must be destroyed at all costs, they argued, even if it meant the displacement of the Gaza Strip’s entire population.

What long sounded like an absurd conspiracy theory could now actually be facilitated by the war and relentless military force: the eviction of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from Gaza and even the first concrete steps towards establishing a rump Palestinian state in North Sinai. Although Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has expressed resolute opposition to such a scenario, developments on the peninsula since 2014 raise a number of questions and, in light of the course of the war to date, are more than a little concerning.

The Dogs of War

The north of the strip and the City of Gaza itself have already been largely destroyed and will most likely remain uninhabitable for an indefinite period of time. Overshadowed by the intensity of the war, statements by influential Israeli security officials mapping out gloomy scenarios for the post-war future so far hardly register in international media. Yet the long-held dream of Israeli hardliners and Zionist settlers to completely expel Gaza’s Palestinian population has never seemed as close as it does today, and the demeanour of their advocates has never been as aggressive.

On 17 October 2023, the Misgav Institute for National Security and Zionist Strategy published a paper openly advocating for the “relocation and final settlement of the entire Gaza population” in Egypt. The report refers to “ten million available apartment units” in Egypt, “of which half were built and half are under construction”. These could house up to 6 million people, while the resettlement itself would cost somewhere between 5 and 8 billion US dollars.

Shortly afterwards, an Israeli website leaked an internal government report discussing the systematic displacement of the entire population of Gaza to North Sinai in the aftermath of an Israeli ground invasion. Following the erection of tent cities for displaced Palestinians southwest of the Gaza Strip, a “humanitarian corridor” would be established, followed by the construction of new cities in Sinai. At the same time, a “sterile zone” south of Rafah several kilometres wide would be created, “so that the evacuated residents would not be able to return”. “Uprooted” Palestinians were to be “absorbed” by other countries, with Canada, Greece, Spain, and states in North Africa mentioned as possible candidates.

Meanwhile, Giora Eiland, head of Israel’s National Security Council from 2004 to 2006, has also returned to the stage. Since the beginning of the war, he has published a series of articles retooling ideas he propagated 20 years ago, including the “disproportionate and intentional destruction of civilian infrastructure and populations”, combined with the proposal to forcibly “transfer Palestinians to Sinai into a single vision”, as the Egyptian media outlet Mada Masr summarizes Eiland’s latest writings. “Israel needs to create a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, compelling tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands to seek refuge in Egypt or the Gulf”, he wrote in a recent “opinion piece”. His declared goals: the elimination of Hamas as a military and governing body in Gaza, and the displacement of the strip’s entire population.

In another text, Eiland even compared Gaza to Nazi Germany, explaining that a war between states is not won by military combat alone, but above all by “breaking the opposing side’s system”. Israel should therefore under no circumstances “provide the other side with any capability that prolongs its life”, an explicit reference to the delivery of energy and fuel. “The way to win the war faster and at a lower cost for us requires a system collapse on the other side and not the mere killing of more Hamas fighters”, the former general opined. “We must not shy away” from a “humanitarian disaster in Gaza and severe epidemics”, as, after all, “severe epidemics in the south of the Gaza Strip will bring victory closer and reduce casualties among IDF soldiers”.

An Old Colonial Fantasy

These “old colonial fantasies”, as Mada Masr calls them, have been around since the 1960s. They first emerged shortly after the Six-Day War in 1967, which ended with Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, Sinai, and the Golan Heights. At the time, Israeli cabinet members suggested transferring the population of Gaza to the West Bank and Jordan in order to make way for an Israeli annexation of the strip. Around 1970, Israel briefly tried to incentivize Palestinians from Gaza to move to Israeli-occupied al-Arish in Sinai, a strategy that was already abandoned by the mid-1970s.

Eiland and Israeli professor Yehoshua Ben-Arieh propagated a new version of these plans in the early 2000s, proposing a land swap between Israel, Palestine, and Egypt. Egypt was to hand over a part of North Sinai to the Palestinians in order to create something like a Greater Gaza, while Israel would cede parts of the Negev desert to Egypt. It was not until 2014 that the Israeli army radio network, Galatz, warmed up the idea again and claimed that such a “solution” could accommodate all Palestinian refugees and satisfy the “right to return”. In the same year, the President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, stated that el-Sisi had proposed such a deal, but denied the reports shortly after and only admitted that Egypt’s ex-President Mohamed Mursi, overthrown in the bloody 2013 military coup, had offered Abbas land in northern Sinai in 2012.

In 2017, Egypt’s former President Hosni Mubarak, ousted in the 2011 revolution, publicly denied a BBC Arabic report that Mubarak had agreed to take in Palestinian refugees displaced in South Lebanon in talks with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1983. However, Mubarak admitted that Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had again suggested settling Palestinians in North Sinai as part of a land swap deal in 2010, a proposal that Egypt’s aging ex-dictator flatly rejected, according to his statement.

The colonial fantasy gained new momentum when Donald Trump took office in 2017. After his administration moved the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, a harsh provocation to the Palestinian side, Trump appointed son-in-law Jared Kushner as special envoy for the region, organizing a conference in the Gulf monarchy of Bahrain in 2019 to raise funds for an initiative now known as the “Deal of the Century”.

Among the Arab public, the move was seen as a cheap ploy to pay Arab states to take in Palestinian refugees. In contrast to the pragmatic 2002 Arab Peace Initiative, which proposed a Palestinian state within the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital and a land swap between Palestine and Israel to tackle the settlement issue in return for Arab recognition of Israel, Trump’s move was perceived as a further affront to the Palestinians, as it gave Israel a green light to annex the Jordan Valley and legalize illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank.

The Limits of Solidarity

The way the war has played out so far exhibits alarming parallels to the scenario promoted by Eiland. Little surprise, then, that Egypt’s authoritarian president el-Sisi has repeatedly emphasized his opposition to the idea of resettling Palestinians in the Sinai.

He warned against the “liquidation” of the “Palestinian cause” and a departure from the “two-state solution” only days after the war began. The eviction of Palestinians to Sinai would pose an unacceptable security risk, as it would relocate Palestinian resistance to Egypt, turning Sinai “into a launch pad for operations against Israel” and potentially provoking a military escalation between Israel and Egypt. Media outlets under the direct control of Egypt’s intelligence services have since addressed the threat of this so-called “Eiland plan” extensively, of course highlighting el-Sisi’s staunch opposition to such scenarios, as Mada summarizes the public debate in Egypt.

Such clear opposition, at least verbally, is not surprising. Egyptians are overwhelmingly united in solidarity with Palestine, and presidential elections are to be held in December. Those will neither be free nor fair, with el-Sisi’s re-election a mere formality. Nevertheless, in the current political and socioeconomic situation, even considering or not strictly opposing the eviction of Gazans to Egypt would almost inevitably boomerang on el-Sisi and could even provoke protests against him, disrupting the upcoming election charade.

In reality, the solidarity with Palestine proclaimed by Arab elites has long rang hollow. Such solidarity remains strong on the streets from Morocco to Yemen, but pragmatism has long guided the region’s ruling elites. Gamal Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arabism is long dead. Palestine solidarity is propagated by those elites only when it is useful for political reasons, such as during election campaigns, in times of dwindling political legitimacy, or during social and economic crises.

Preparing the Ground

Preparations for expulsions and resettlement from Gaza to the north of the peninsula have been underway since 2014 on the Egyptian side of the border, where el-Sisi’s regime and the Egyptian military appear to have successfully created the preconditions for precisely such a move.

Egypt’s army is currently waging a bloody war in North Sinai against a radical Islamist militia, Wilayat Sina, a division of the self-proclaimed Islamic State (IS). The group is responsible for the brutal murder of hundreds of Egyptian security forces and civilians as well as targeted attacks on Christians, and has claimed responsibility for the attack on a Russian passenger plane that left 224 people dead in late 2017, along with the unprecedented massacre outside a mosque in Bir el-Abd in the western part of North Sinai in which over 300 people were killed. Egypt’s military has failed to restore security for years despite deploying tens of thousands of soldiers to the region.

At the same time, the military is accused of arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances of civilians, torture, and extrajudicial killings of alleged IS fighters. Rights groups such as Human Rights Watch and the Sinai Foundation for Human Rights have documented countless human rights violations committed by Egyptian military authorities and Wilayat Sina against North Sinai’s population.

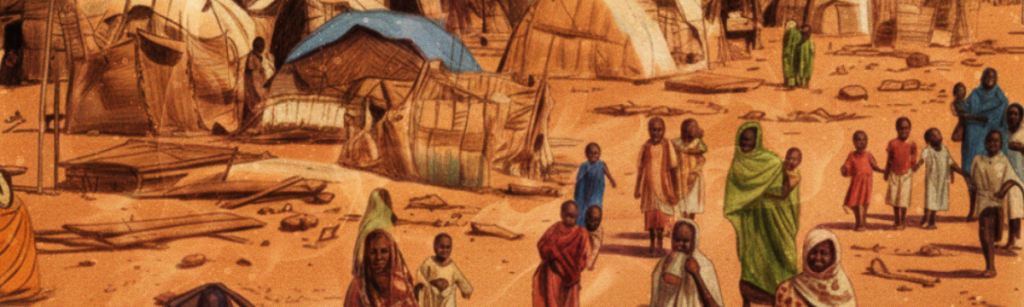

Tens of thousands of people have been displaced or fled in the face of terror, curfews, massive disruptions to water and electricity supplies, and food shortages. Violence against the civilian population as well as the systematic demolition of houses in the Egyptian part of Rafah on the border with Gaza and the cities of al-Arish and Sheikh Zuweid have displaced up to 150,000 people since 2014 — one third of the total population.

Citing the alleged flow of weapons from Gaza to the IS through cross-border tunnels, Egypt issued two decrees designating a buffer zone of five to seven kilometres south of the border to Gaza and classifying the area as a restricted military zone. The decrees also contained provisions on the zone’s “evacuation” as well as compensation for the people living here, who were to be gradually driven from their homes in the years to follow. The Egyptian city of Rafah, with its population of about 75,000 people, was literally razed to the ground. According to Human Rights Watch, at least 12,350 buildings were demolished between 2013 and 2020, most of them in Rafah and al-Arish and surrounding villages.

El-Sisi issued a new presidential decree in 2021, massively expanding the restricted military zone on the border with Gaza from 79 to 2,655 square kilometres. In the same month, the Sinai Foundation for Human Rights reported the construction of a six-meter barrier resembling a border wall east of al-Arish, apparently built along the newly established restricted zone that separates the surrounding areas of Rafah from the eastern foothills of al-Arish and the military airport located here.

According to Human Rights Watch, evictions have not been carried out in accordance with international law. Moreover, although the Egyptian government promised residents compensation, little has been forthcoming. The provision of alternative housing in places like the long-delayed urban development project New Rafah, or the right to return promised by Egyptian officials for displaced people from villages outside the restricted zone in Rafah, have led to tensions between the state and local civilians for years, sparking regular protests and even clashes, most recently in October 2023. Six Egyptian human rights groups recently issued a statement linking the state’s violent crackdown on the protests in late October to the current carnage in Gaza, and sounding the alarm about the forced displacement of North Sinai’s inhabitants and the feared transfer of Gaza’s population to Sinai.

No Future for Gaza

In light of the persistent Israeli calls for the expulsion of Gaza’s entire population, but also the interplay between developments in North Sinai since 2014 and the ongoing war in the Gaza Strip, a number of uncomfortable questions arise.

Was the Hamas attack a welcomed pretext for extremist forces in Israel to push for the mass displacement of Palestinians, particularly given reports that Netanyahu’s government ignored warnings of an imminent attack? To what extent has Egypt’s regime created the preconditions in Sinai for mass expulsion, thereby leaving the door open for multiple scenarios? Could we be witnessing the first steps towards another mass displacement of Palestinians, this time to North Sinai?

The establishment of a Palestinian state in North Sinai in the short or medium term is likely unrealistic, regardless of el-Sisi’s depopulation policy in North Sinai. A land handover in Sinai, necessary for such a scenario, is simply not feasible in Egypt in the near future. The 2016 handover to Saudi Arabia of two uninhabited Red Sea islands in the Gulf of Aqaba, Tiran and Sanafir, demonstrated how Egypt’s public would react to a transfer of land in Sinai. Not only the opposition, broken by years of ruthless repression, but even influential parts of the Egyptian elite outspokenly rejected the island deal.

The displacement of tens or even hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from Gaza to Sinai, on the other hand, is a very real possibility. An end to the ongoing violence is not in sight — the Israeli army seems determined to continue its air and ground offensive, making life in large parts of the occupied Gaza Strip de facto impossible. If Israel’s allies, above all the US, do not stop Netanyahu’s warpath, the only remaining way out for the Palestinian civilian population will sooner or later be to flee to North Sinai, a scenario that appears more likely by the day as Israel expands its shelling of southern areas of the Gaza Strip.

While Egypt continues to oppose such a move, at least rhetorically, no effective opposition can be expected from the Palestinians’ supposed allies across the Arab-Islamic world. Libya, Sudan, and Yemen are riven by armed conflicts between rival militias and armies. After years of war and Turkey’s occupation of parts of its territory, Syria is in a state of military and economic decline, neither willing nor capable of opening a northern front with Israel. Meanwhile, Hezbollah, supported by Iran, has no interest in getting involved in an open war with Israel, while el-Sisi’s military regime is primarily interested in its own political stability, for which it must keep Egypt’s population under control at any cost. Its current display of solidarity with Palestine is an opportunist gesture, but little more.

Meanwhile, as the Israeli army expands its assault from the skies further into the south of the Gaza Strip, the prospects for over 2 million Palestinian civilians who call Gaza home are grimmer than ever. Indeed, should the most extreme elements of the Israeli establishment have their way, they may not call it home for much longer.