The Geopolitics of Sport in North Africa: “From the diplomacy of briefcases to that of Sneakers”

The Geopolitics of Sport in North Africa: “From the diplomacy of briefcases to that of Sneakers”

Since time immemorial, sports and politics have been intricately linked. One need only look at the Olympics in ancient Greece. Indeed, sports have been frequently used as a diplomatic channel in the past: ping-pong between the US and China, hockey between Canada and the USSR, and the wrestling diplomacy between Russia, Iran, and the USA. Cricket diplomacy between Pakistan and India, too, is a perfect example of negotiations between brothers turned enemies. There were also those baseball diplomacy instances between Cuba and the US. But what about the geopolitics of sport in North Africa?

In all the aforementioned examples, sport was used for national interests. Similarly, the political leaders of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia were aware, quite early on, of the importance of sport as a pillar of national identity. Indeed, in 1956, the day right after the declaration of independence, Habib Bourguiba, the former president of Tunisia said: “We really need to participate in sports competitions, be they Arab, Mediterranean, or international […]. The prestige of athletic accomplishments is undeniable. It reflects on the nation as a whole”[i]. The president of the Tunisian Republic understood that sports and diplomacy can both be played on the same leg with so many political actors engaged in diplomatic practices and so many diplomats engaged joining official dialogue to the Athletic world.

Sport is the field of pacific or regulated confrontation between nations. It’s the most visible way to hoist the national flag on the international scene. The Mediterranean games of Algiers 1975 and Casablanca 1983 revealed the bitterness felt towards the French colonizer. Hassan II’s Morocco and Houari Boumediene’s Algeria both expressed strong nationalism in the context of tense relations between the Arab World and Israel. The lavish opening ceremony of the Algiers games was meant to demonstrate the “grandeur” of the young Algerian nation. The Algerian football team’s victory against France was viewed, then, as a revenge against the former colonizer. This victory was celebrated like a “second independence” by the Algerians[ii]. Let’s not forget that the ex-Algerian international Rachid Makhloufi received, in 1968, the football Cup of France directly from the hands of General De Gaulle who said to him: “You are France”.

National sentiments are exacerbated, and football offers a fertile ground for the affirmation of collective identities as well as local or regional antagonisms since “every match is a confrontation that takes the form of a ritualized war. Football gives free rein to imaginary projections and patriotic fanaticism”[iii].

In 1983 in Casablanca, the opening ceremony of the games insisted on rooting the Cherifian kingdom in the wider Arab-Muslim world. This was in part in solidarity with Lebanon but also to pay homage to Saudi Arabia[iv]. Athletic competitions took place in a climate hostile to France: some French athletes refused to participate in the closing ceremony. Indeed, back then, the French ambassador complained to the Moroccan government of the Francophobic attitude that part of the Moroccan public exhibited.

Sport is also a tool of economic diversification, making it a fundamental instrument in meeting socio-political challenges. It’s also a major soft power instrument[v] used to strengthen the brand name of a country. Indeed, from Paris-Saint-Germain[vi] to World Cup 2022 has fully deployed its influence strategy. Although Doha has long been criticized for the ambivalence of its geopolitical positions in the middle east, it has conferred upon itself a certain legitimacy by investing in sport. This small country with a modest demography has managed to become very important on the international and media scene thanks to its policy of hosting major sporting events.

The World Cup has often been subject to the games of influence and power. Football, more than any other sport, has global popularity. All states with legitimacy issues turn to football, a true sport of the masses, with the hope of obtaining political benefits.

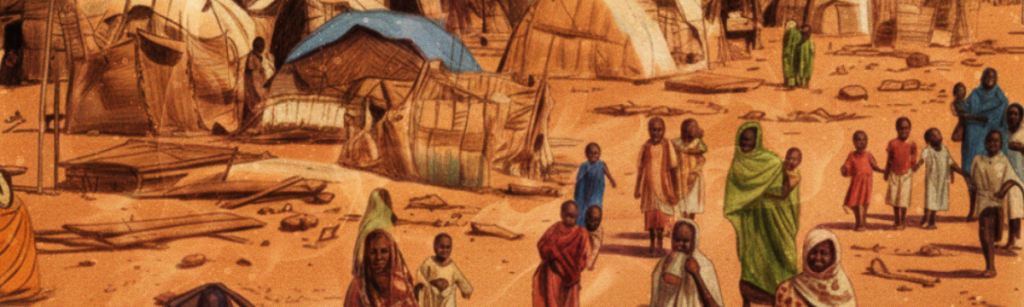

In Algeria, football has never been too distanced from politics. Even before Algeria’s independence, the FLN team, not recognized by FIFA, played from 1958 to 1962 a considerable militant role through innovative political marketing and athletic diplomacy. The best football players of Algerian origin secretly abandoned, in 1958, the French championship to establish, in Algeria, the team that would go on to become a symbol of the country’s struggle for independence. During the 2019 AFCON in Cairo, the Algerian authorities marshalled 6 military aircrafts to transport fans to support the national team[vii]. Similarly, Algerian authorities created a true airbridge to Khartoum, Soudan in 2009 for 2010 World Cup qualification match between Algeria and Egypt. This allowed the transport of 15000 Algerian supporters in a record time and kept the morale high before and during the match[viii].

In international relations, the concept of power governs both states and sport. Football constitutes a pillar of nation’s radiance and has become a keystone of soft power. Sport diplomacy relies on sport as a vehicle of soft power. A state can derive the “sympathy” and establish a link with international public opinion. Indeed, great athletic competitions unrivaled ability to mobilize the masses proves that the link between sport and soft power is an intuitive one. The use of sport as a source of soft power was renounced at times as sports-washing. However, every “national brand becomes more credible when it’s worn by athletes” as the former British ambassador Tom Fletcher once summed it up[ix]. Major sporting events have become the perfect pretext for backroom diplomacy as diplomats use these occasions to discuss &and resolve matters that are far removed from sports. Sport, then, is not something exclusive to athletes but, rather, a stadium for actors of athletic diplomacy as well as it involves national and international governance institutions, NGOs, multinational sponsors, media coverage, and, most importantly, spectators both physically and through televisions. Officials of diplomacy can no longer ignore the sporting world.

Although it saw its value dip in the past, sport is being pursued by Maghreb countries today as a tool for improving foreign relations and reaching the foreign public more effectively as well as reinforcing their image and international influence.

The stadium has become a space for influence where states can treat with decision makers from around the world. Sport has also become the surest way for a country to unite a nation behind a national or regional project and can replace the force of arms in a warlike context. In the Maghreb, diplomatic tensions between Morocco and Algeria are higher than ever and the rivalry between the “brothers-enemies” are hampering, among other things, regional integration projects such as the Arab Maghreb Union. Nevertheless, Moroccan sports federations were able to participate in the Mediterranean games (MG) of 2022 which took place in Algeria despite the breakup of diplomatic ties between the two countries.

Sports, in a globalized public space, legitimize the international actions of a country and represent a factor of power. Morocco, for example, tops the ranking Maghreb in the Global Soft Power Index 2022.

A national team’s victory solicits admiration and respect. A sportsman, then, is a diplomat wearing shorts. Morocco, in 1986 in Mexico, became the first African team to qualify for the second round of the World Cup although it lost in the 8th finals against Karl-Heinz Rummenigge’s Germany[x]. Rummenigge’s team lost to the national Algerian team during the 1982 World Cup in Spain. Although it was Algeria’s first participation in the world cup, Algeria was the first African team to defeat a European team. With its legendary players Rabah Madjer and Lakhdar Belloumi, Algeria taught the German team a lesson in humility and accomplished one of the greatest feats of the tournament[xi].

Football has become a universal social activity that catches the hearts and souls of a billion human beings and occupies a major position in the geopolitics of sport in North Africa. This, however, does not mean that athletics and swimming are in the cold.

The Tunisian swimmer Oussema Mellouli’s accomplishments in the Beijing Olympics of 2008 and London 2012 were disproportionate to the geopolitics of the nation. On August 17th, 2008, Mellouli won his first Olympic title in the 1500 meters freestyle swimming competition in the Chinese capital, ending Tunisia’s 40 years wait for the title. Tunisia’s first and last Olympic title dates to 1968. It was won in Mexico City by Mohammed Gammoudi in the 5000 races. He had already won for Tunisia its first silver medal in the Olympics held in in Tokyo in 1964. He is Tunisia’s most decorated Olympic athlete. Uchronically speaking, Gammoudi could have won a medal in the 1976 Montreal Olympics were this edition of the Olympics not boycotted by the African nations in protest against the presence of South African athletes where the regime was practicing apartheid. Following the Arab revolutions, Gammoudi took up honorous responsibilities within the Tunisian Federation of Athletics.

Although the road ahead is still long, female sports are progressing and represent an element of women emancipation in North Africa. Having previously won a gold medal in the first 400m female hurdling in the history of Olympic games in LA in 1984, the Moroccan athlete Nawal El Moutawakel became a sports manager and politician. Today, she is executive board member and vice president of the International Olympic Committee and was president of the coordination committee for the 2016 Olympics in Rio 2016. Similarly, the Algerian fencer Salim Bernaoui had, starting 2013, headed the Algerian Federation of Fencing after having represented Algeria in 1996 and 2004. High level athletes often find in sport a chance for social promotion. Hassiba Boulmerka represented a civil-war-torn Algeria which seemed on the path to Islamization by the sword in the Barcelona Olympics of 1992 and won the country its first gold medal in the 1500m race. This inducted Algeria into the hall of the countries with at least one gold medal. Boulmerka’s victory caused jubilation throughout the black-decade-suffering the country. But it also brought her the wrath of the radical Islamists who don’t tolerate the success of a woman in high level sports. Great athletes can also be very critical of their federations. The Algerian twice gold medalist Taoufik Makhloufi accused sports decision makers in Algeria of sabotage and had to spend his life in exile. The Olympics were often an occasion for athletes to speak against management issues that plague federations, Olympic committees, and ministries and these athletes often ended up being shunned and denigrated in atmospheres characterized by censorship. This proves that sport can also be an arena for airing political grievances which can be heard loud and clear since the Olympics and the other international competitions are the focus of all microphones and cameras.

In the Maghreb countries as well as the others, federations are not always run with perfect transparency. Athletes with “sneakers instead of briefcases, but still diplomats”[xii] engage in a form of diplomacy that blends representation with communication and, sometimes, even negotiations. Elite athletes with a cross-border fame always represent something: a nation, a club, a renown, or the political vision of a country. One such example of what could have been a good fusion between political vision and sport was the case of the footballer and son of head of state Al-Saadi Kadhafi. He was the son of the former Libyan leader. Using his political status as a springboard, he did everything, including investing in Serie A clubs, to eventually play, in 2014, for 15 minutes with AC Perugia against Juventus. It was a true 15 minutes of glory for him[xiii].

The latest Mediterranean games of 2022 in Algeria were a true geopolitical moment. Algeria hosted these games right after having been crowned champion of the Arab Football Cup in 2022 in Doha. They took place from June 25th to the symbolic national date of the Independence Day of July 5th. The Mediterranean games can be considered “mini-Olympics” as they gather 26 years from the Mediterranean zone, including France. The International Committee for the Mediterranean Games chose the city of Oran for this 19th edition. It took, then, nearly half a century for this competition to return to Algeria after the Algiers edition of 1975.

A grandiose opening ceremony was held for the 2022[xiv] edition with hundreds of artists and musicians participating to exhibit the scenery, history, and influence of the country in the Mediterranean region. Algerian authorities seemed to have taken inspiration from the Qatari model. But will Algeria be able to use sports diplomacy to settle its difference, notably with Morocco, and promote a soft power for its ambitious Algeria tomorrow plan and to make the country one of the biggest economies in Africa?

One would have thought that with some political will, the latest instability in the Franco-Algerian relations, the 9th of its kind in the troubled relations between the two countries, would have found a conclusion in the games. As a soft power tool, sport can significantly contribute to good relations between countries. President Tebboune’s invitation the reelected French president for the opening ceremony would have been a positive signal that the Franco-Algerian relations are headed to the Paris’ desired relaxation. However, it was the Qatari prince who was the guest of honour. The Turkish vice president, the Italian minister of interior, and the Italian sports minister too participated the opening ceremony. In February 2022 in Algiers, the Italian Foreign Minister met his Algerian counterpart as well as the minister of Energies to reinforce bilateral cooperation on Energy procurement[xv].

Relations between Paris and Algiers, two of the great capitals of the Mediterranean, is not a thing of the past. But these relations need to be put behind with all the mistakes of the past to draft a much-awaited Franco-Algerian treaty of friendship. Emanuel Macron has been reelected with this perspective a pillar of his new mandate. Will Macron and Tebboune be the new De Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer and allow the two peoples to look, together, ahead[xvi]?

The Mediterranean Games seem like a political victory for Algeria and the Algerian authorities have predicted an unprecedented media campaign. The campaign was toneless at first and raised the question over whether Algeria really wanted to use the event to embellish its image internationally. The Algerian president, therefore, appointed Mohamed Aziz Derouaz new commissioner for the Games to give them a new start. The progress in the construction of sports infrastructures worried the International Committee for the Mediterranean Games. But Algeria managed to catch up and showed its ability to host major sports events. The Oran Athletic Complex was a notable success as it was constructed with the use of the latest technologies and using modern architectural norms and green energies.

The Mediterranean Games have lost some of their splendor. Although they are a sporting event where countries of the southern hemisphere enter their best athletes, countries of the north, France included, send their more modest athletes. However, had France sent its best sportsmen to Algeria, the Algerian authorities would have surely appreciated the gesture and it would have been an opportunity for a more than welcome truce in the Franco-Algerian ties. Unfortunately, this truce is yet to be reached. In fact, the Games saw an incident: the French football delegation was, alas, booed by the spectators present in the Oran stadium. The situation remains in development and the damage incurred by the Franco-Algerian relations is yet to be assessed.

All this is costing the two Mediterranean powers real opportunities for partnership on sports engineering and the hosting of sporting mega events[xvii]. France is at the heart of sport diplomacy with its hosting of the Female Football World Cup 2019, the Rugby World Cup 2023, and the Paralympic Games in 2024. In this regard, France is leading the way in Europe as it has institutionalized the position of Ambassador for Sport[xviii] and its continuing success in attracting the biggest sports games.

Algiers can benefit from France’s influence to deepen its sports politics and harvest real benefits on the economic as well as the social levels, notably vis-à-vis the youth in a post-hirak[xix] Algeria[xx]. For example, the French embassy in Mauritania and the National Olympic and Athletic Committee of Mauritania have on November 18 and 19, 2022, in the Institut Francais in Nouakchott “open door” days on sport in Mauritania[xxi].

If Algiers envisions applying to host the World Cup, France could be a natural ally. It remains to be seen, however, if the Algerian government is ready to make this a national priority and to make sport, along with other tools, an element of valorization and a positive renown for the country. Morocco, on the other hand, aspires to make of hosting the World Cup a national priority. After five failed attempts, Morocco has announced, via its minister of sport Rachid Talbi Alami, that it will apply to host the 2030 World Cup[xxii]. Morocco aspires to be the second African country, after South Africa in 2010, to host the football event. Rabat sees this as a catalyst for development in the country.

Will we see a competition, like the arms race between the USSR and the USA in the 1980s, between Algiers and Rabat, or, as necessity is the mother of invention, a pooling of political, financial, and influence resources between Morocco, Algiers, and Tunisia to host the Cup? The right to host the 2026 World Cup was granted to the US/Canada/Mexico trio. In the long run, the Rabat/Algiers/Tunis trio could combine forces to host the World Cup or the Olympic Games.

In addition to the economic aspect, politics play a major role in the scramble to host the Olympic Games. Ever since their creation in 1896, the Olympics have never taken place in Africa although this global event has made the world tour, from LA to Tokyo, and, soon, Paris. No one says it’s time the Olympic torch shined its light on an African capital. The Algiers, Rabat, and Tunis trio could offer it its first African home.

While the EU studies its new pro-sport policies, what sort of place will sports diplomacy have in the Maghreb countries which are still under-developed? And will these countries establish a strategy for a long-term goal? The sports and diplomacy duo are still in its infancy and without a ceiling. Whereas the Maghreb possesses several assets and talents that remain largely under-exploited.

Bibliography :

Jean-Marie Brohm, « football et passion politique », Le monde diplomatique, une manière de voir, mai-juin 1998.

Ignacio Ramonet, « Sport et nationalisme », Quasimodo n° 1 octobre 1996, Montpellier.

Pascal Boniface, Géopolitique du sport, Paris, Dunod, 2021.

Jean-Baptiste Guégan, Géopolitique du sport, une autre explication du monde, Bréal, 2017.

Maxence Fontanel, Géoéconomie du sport, le sport au cœur de la politique et de l’économie internationale, L’Harmattan, 2009.

Mazot Jean-Paul & LAGET Serge, Les Jeux méditerranéens (1951-1993), Presses de Languedoc, 1992.

Fates Youcef, Sport et politique en Algérie, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2009.

Darby Paul, Africa, Football and FIFA: Politics, colonialism and Résistance, London, Franck Cass, 2002.

[i] Habib Bourguiba, « le rôle du sport dans la bataille contre le sous-développement », A speech by president Bourguiba on September 30th in Tunis.

[ii] In the end, Boumedienne told the players that he did not wish for the Marseillaise to be heard all over the Algiers stadium « for my own honour and the honour of our nation».

[iii] Statements by Ignacio Ramonet, former director of the French Monthly Le Monde diplomatique, Ignacio Ramonet was born in 1943 in Spain but grew up in Morocco. After obtaining the maîtrise de lettres degree in France, he taught at the College du Palais royal de Rabat where he educated the future king, Mohammed VI. As a writer, he published numerous works, among which, Géopolitique du chaos (Galilée, 1997/1999), La Tyrannie de la communication (Galilée, 1999), Guerres du XXIème siècle : Peurs et menaces nouvelles (Galilée, 2002)….

[iv] Saudi Arabia gave substantial financial aid to Morocco for the construction of sports facilities.

[v] The concept of soft power was put in place by the American Joseph Nye since the end of the cold war. It is defined by a state’s ability to orient and influence international relations in its favour through means other than the threat of force. This influence is exercised on opponents as well as allies and targets all levels of international relations. Diplomacy, alliances, institutional or non-institutional cooperation, economic aid, cultural attractiveness, and the propagation of education are the primary values of soft power. Soft power is a set of pacific tools to convince other international relations actors to act or position themselves one way or the other.

[vi] The Parisian club used to belong to Colony Capital, an American investment fund with financial difficulties. It’s director general for Europe, Sébastien Bazin was close to Nicolas Sarkozy. His daughter was one of the children taken hostage at the Ecole Maternelle de Neuilly-sur-Seine (France) in May 1993, the town of which Sarkozy was mayor. In June 2011, the Qatar Sports Investment investment fund spent 76 million euros to buy the club. Nicolas Sarkozy denies having mediated for Qatar to buy the Parisian club. Later on, on December 2nd, 2010, Qatar was awarded the right to host the World Cup.

[vii] Algeria was crowned champion Africa during the 2019 AFCON following its victory over Senegal in the final game. The Fennecs won the 2019 AFCON 29 years after their last trophy in 1990.

[viii] https://www.jeuneafrique.com/792067/societe/can-2019-la-rivalite-algerie-egypte-et-lombre-doum-dormane/.

[ix] Tom Fletcher is the former British ambassador to Lebanon (2011). He was described as disruptive and « broken centuries of protocol» according to The Telegraph. Graduated from Oxford, Fletcher served as foreign affairs advisor to three consecutive prime ministers: Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, and David Cameron. He wrote Naked Diplomacy, Power and Statecraft in the Digital Age which describes the diplomatic practice and the representation of the state in the age of the internet and the blurring of states’ borders.

[x] Karl-Heinz Rummenigge was born on September 25th, 1955 in Lippstadt in Western Germany. He’s a German international footballer and is considered one of the greatest attacking players in the history of German football as well as one of the best players in the 80s. He was a symbol of Germany’s domination of European and world football in the early 1970s and through the 1980s.

[xi] The Germans were the favourite side against Algeria and were threatening the Algerians with a crushing defeat. Rummenige had two ballon d’ors. He had, on his side, world class players like Breitner Europe’s second best player. Germany, then, was already thinking about the final game. Derwall, Germany’s national coach, said he’d go home on one foot if his team lost. The Algerian selection, on the other hand, was more modest. It was made up, in its majority of local championship players. It was then, a universal surprise that the Mannschaft lost 1-2. Still, Germany arranged with its Austrian neighbour to end the match on a draw during the second phase of the competition which guaranteed both teams qualification. Journalists would, later, recall this as “the shameful match».

[xii]Thus was the England national team described on its way to the football world cup in Brazil in 1950. The lukewarm performance of the English team, with a 0-1 defeat against the US, is remembered with sorrow.

[xiii] https://archive.nytimes.com/goal.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/25/a-qaddafi-son-italian-soccer-and-the-power-of-money/

[xiv] Around 3 400 athletes representing 26 countries from 3 continents (Africa, Asia, and Europe) played against each other in 24 sports, from Athletics to swimming as well as football, judo, and gymnastics.

[xv] Algiers has become a much-courted capital in light of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict. Many European countries, notably from the Mediterranean zone, want to guarantee their gas supply. Algeria is the closest Energy power to Europe. France is trying to position itself in the scramble for Algiers.

[xvi] Will this future look like the one designed through the Elysée Treaty by France and Germany.

[xvii] Brazil, Russia, South Africa, and China, too, have realized that sporting mega events can be opportunities to present a « new » or « better» face on the international arena. These four nations are part of the four countries that make up the BRICS club and Algeria has applied for membership of this organization.

[xviii] Laurent Fabius, foreign minister, initiated a strategic « revolution » in January 2016 with the nomination of an ambassador for sport and the creation of a sport diplomacy for the influence of France.

[xix] Popular revolt against the regime of Abdelaziz Bouteflika that started on February 21st, 2019.

[xxi] With the participation of high-level athletes, clubs or federations managers, and academics and journalists, both from Mauritania and France, sought to promote the economic and job-creating potential of sport. Sport is also a pretext for France to be able to preserve its sphere of influence in North Africa, and more largely, in the Sahel.

[xxii] According to Moroccan cabinet statement, the Emir of Qatar informed King Mohammed VI of his support in case Morocco tables its application to organize the 2030 world cup.