Refugee Regime in Upheaval

Algeria has followed Egypt’s path and started drafting an asylum law. Yet, such a law will neither improve the precarious situation of people on the move nor effectively counter Algeria’s deportation practices

The architecture of northern Africa’s migration control set up and the overall refugee regime currently in place is about to undergo substantial transformation ―with potentially far-reaching consequences. After years of unsuccessful attempts by the EU Commission to persuade North African countries bordering the EU to adopt asylum laws, Egypt surprisingly and swiftly pushed such legislation through its institutions in 2024. In December, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ratified the vaguely worded bill that is would transfer Refugee Status Determination (RSD) and asylum recognition procedures from the UN refugee agency UNHCR to the Egyptian state. The UNHCR office in Algiers has now also confirmed, for the first time, that Algeria’s government, too, is working on such legislation.

“While UNHCR is not directly involved in the drafting process, we continue to offer technical support and expertise to the Algerian authorities to align the legislation with international standards”, the UN agency’s Algeria office told the RLS in an email. “Discussions are ongoing to determine the most effective ways UNHCR can contribute to this process. At this stage, we do not have information on a specific roadmap or the content of the proposed law”, the email reads.

The legislative process is clearly still at a very early stage. Algerian government officials first announced their intention to draft such a law during the 2023 edition of the Global Refugee Forum, a UNHCR conference held annually in Geneva. A strategy paper published by UNHCR’s Algeria office in January 2025 vaguely states that the asylum law that the UN agency “will endeavor to expand access to asylum, registration, and documentation” in Algeria, either “jointly” with the government or “by the government”. In fact, UNHCR’s role remains unclear once these laws take effect, both in Algeria and Egypt. In Cairo, too, there is still a lack of clarity regarding UNHCR’s future role, as in addition to the law that has already been ratified, bylaws to the legislation are to be adopted too. However, so far, the government has neither drafted nor adopted the necessary bylaws.

European Deportation Fantasia

Meanwhile, the EU―jointly with UNHCR―has been actively promoting drafting processes for such laws in the region since the 2010s. After Algeria had worked on a draft asylum law as early as 2012, Morocco finalized a draft bill in 2014 while Tunisia presented a draft in 2017. In all three cases, however, the drafts were never submitted to the respective parliament for a vote or to the government for ratification; ultimately, all three projects were shelved. EU states hope that such legislation would enable them to externalize asylum procedures to northern Africa and thus stem the flow of people on the move towards Europe. According to the Dublin regulation logic, it would be easier for European states to classify authoritarian states as “safe” if asylum laws were to be put in place here.

However, European fantasies of deporting third-country nationals to North African “transit states”―as the border regime jargon so nicely puts it―can be ruled out for the time being given the firm refusal of the governments in Cairo, Algiers or Tunis to play along. Proposals to set up ‘disembarkation platforms,’ hotspots, or externalised asylum processing centres run by EU states in Northern Africa—ideas floated regularly since the early 2000s—continue to be rejected by North African governments.

Coordinated Migration Control

Despite this staunch resistance to certain elements of the European border externalization to the southern shores of the Mediterranean, North African governments are willingly integrated into the EU border regime in other areas. Regarding deportations, for instance, authorities in Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia , or Libya are acting entirely in line with European migration control policies. Additionally, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya are now increasingly coordinating their (anti-) migration policies with each other as well as within the framework of a joint alliance with Italy, their key partner in Europe. At a high-level summit in Tunis in April 2024, Algeria’s President Abdelmajid Tebboune, Tunisia’s head of state Kaïs Saïed and Mohamed al-Menfi, who governs western Libya, agreed to , increasingly align their (anti-) migration policies. Just weeks later, the interior ministers of the three states met with their Italian counterpart in Rome, also with the aim of further expanding migration control coordination.

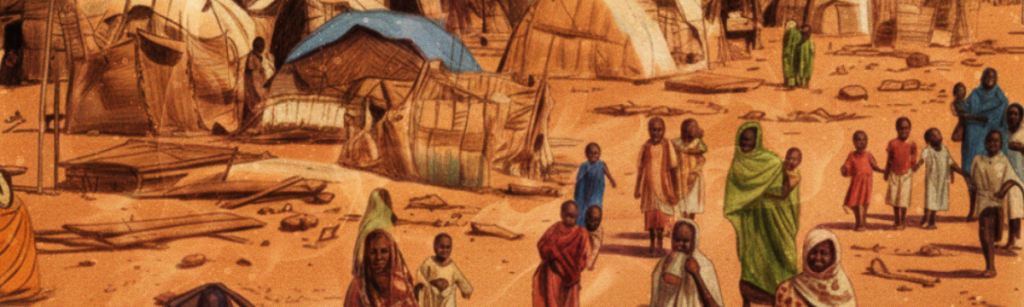

This increasingly institutionalized coordination of reprisals against people on the move was triggered by Tunisia’s sudden turnaround regarding migration control in early 2023. Until then, Tunisia-based people on the move were kept in a state of manufactured precarity as in all other northern African countries, but the Tunisian state remained mostly passive and only deported people to Algeria or Libya via its southern land borders, but only in isolated cases. Since 2023, however, mass deportations to the southern or western borderlands have become routine in Tunisia. According to the World Organization against Torture (OMCT), Tunisian authorities deported more than 9,000 people to the Tunisian-Algerian border and at least 7,000 people to the Tunisian-Libyan border in 2024 alone.

Militias allied with the two competing governments in Tripoli and Tobruk in Libya are also increasingly carrying out mass expulsion campaigns to Chad, Niger or Sudan, while Algeria has continued its systematic mass deportations to Niger, which have been carried out on an almost weekly basis since 2017. At least 31,404 people were deported to Niger by Algerian authorities in 2024, according to the activist network Alarme Phone Sahara. Algeria is now also frequently expelling people to Libya. Since early 2024, at least 1,800 people have been intercepted by Libyan militias at the Algerian border and detained in the city of Ghadames, according to sources who wish to remain anonymous.

All three states have also closed or criminalized almost all civil support and aid infrastructure for undocumented people within their respective territory. In Algeria, almost all organizations that had previously campaigned for the rights of people on the move―above all the Algerian Human Rights League LADDH and the youth association RAJ―were banned by courts in 2022. Aid NGOs such as Caritas, which provided emergency aid to those in urgent need, were also forced to shut their doors for unspecified reasons. While the closure of civic space in Algeria materialized in the context of the counter-revolutionary dynamics following the failure of the “Hirak” (Arabic for “movement”) protest movement in 2020, civil society organizations in Tunisia and Libya were closed down explicitly due to their work with people on the move. In Tunisia, the state deliberately shut down NGOs that had offered emergency accommodation, medical assistance, or legal advice for undocumented people since 2023, and criminalized their leaders. In Libya, the offices of at least ten foreign aid organizations working in the field of migration were forced to shut down as recently as April 2025.

Turning into a mere Service Provider

While almost the entire support and aid infrastructure for people on the move in these three countries has now been or is being shut down and deportations are taking place at a pace rarely recorded before, UNHCR and the UN-associated International Organization for Migration (IOM) may soon be limited to providing only minimal assistance to those in urgent in the near future. Since 2023, even the border regime service provider IOM has had less room to manoeuvre in Algeria and Tunisia, and the organization is increasingly being forced to focus almost exclusively on its de facto core activity in the region: the so-called “voluntary return” deportation operations primarily to West or Central African countries.

Meanwhile, it remains unclear what role UNHCR might play once the asylum laws come into force in both countries. Despite Europe’s deportation fantasies, Algeria and Egypt are pursuing their own― albeit diverging in some respects―goals by pushing forward national asylum legislation. “By adopting such a law, Egypt might want to gain a greater degree of control over refugee and asylum matters, rather than delegating responsibility to UNHCR”, the former UNHCR official Jeff Crisp tells the RLS. “At the same time, the government has an interest in keeping UNHCR involved in asylum-related matters in order to access the international resources that UNHCR is able to mobilize. Additionally, UNHCR’s involvement provides governments with an important degree of legitimacy. It helps them to counter any criticism of the way they treat refugees or asylum seekers”, Crisp says.

Egypt seems to be following the Turkish example, where an asylum law came into force in 2014. According to critics, the law does not offer adequate refugee protection. Instead, it gradually eliminated UNHCR as a decision-making authority on refugee status, and was primarily enforced within the context of nationalist and geopolitical interests, particularly in relation to the Turkey-EU deal.

Selective Refugee Protection

While Egypt also appears to be using its asylum law as a bargaining chip in loan and investment negotiations with its European partners, Algiers, in contrast, is not dependent on loans or financial injections from Western or international partners. It apparently intends to push ahead with such a law to keep a closer eye on UNHCR’s Algeria office in the future. In Egypt, the new asylum bill provides for the establishment of a state authority charged with refugee issues―the Permanent Committee for Refugee Affairs (PCRA)―as, so far, no such entity exists in Egypt. Algeria, on the other hand, has already had such a state agency in place since 1963, the Algerian Bureau for Refugees and Stateless Persons (BAPRA), which is subordinated to Algeria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. With the asylum law, the government now appears to aim at regulating and monitoring the UNHCR’s asylum processing more closely as well, possibly providing BAPRA with a stronger role.

However, neither the law nor a possible future BAPRA with expanded powers will be able to significantly alter Algeria’s selective application of the 1951/1967 international refugee regime ratified by the government. Refugee policy in Algeria has always been a manifestation of the “anti-imperialist strategies of Algerian foreign policy”, while the state’s support for the decolonization of Western Sahara―and to a certain extent also Palestine―remains a “rare relic of Algeria’s anti-imperialist period”, as the political scientist Salim Chena put it in 2011. In fact, the asylum recognition practices of UNHCR and BAPRA precisely reflect this foreign policy appropriation of the international refugee protection regime. While 173,600 people from Western Sahara and 7,866 Syrians have been granted refugee status by UNHCR Algeria, the number of people from all other countries recognized as refugees or asylum seekers by the UN agency has remained minimal. As of 2024, fewer than 3,000 people of other nationalities were recognized as refugees or asylum seekers in Algeria. People who have entered the country irregularly from West or Central African countries, most of whom are seeking work in Algeria, while others continue their journey toward Europe after temporary stays, will have little chance of obtaining asylum or regular residence permits in the future—whether or not an asylum law is in place.