Öcalan buries the hatchet and rekindles Erdoğan’s geopolitical ambitions

The pluridecade-long Kurdish-Turkish conflict has been interspersed with defining moments, amongst which the speeches of Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), hold a distinctive place. In 2013, his call for a unilateral cessation of hostilities signaled a watershed, paving the way for negotiations between the PKK and the Turkish government. Twelve years later, on February 27, 2025, Öcalan reiterated this call for peace, calling on the PKK to disarm in favor of a political struggle, a proposition endorsed by the PKK-affiliated Syrian Democratic Union Party (PYD). Concurrently, the political and military victories of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of Turkey, have consolidated his power, cementing him as a dominant player in the region and expanding Turkish influence in Africa. Potentially rid of the “Kurdish Question”, Erdoğan’s Turkey could pursue its expansionist impetus in three directions: Syria and the Middle East in more general terms; Asia Minor, with a potential fast-track resolution of the dispute over the Zangezur corridor between Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan; and Africa, Turkey’s new Eldorado.

Historical background to the conflict: The PKK assumes control of the “Kurdish Question” (1980-2013)

Tensions between the Kurds and the Turkish state date back to the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923. Under the Ottoman Empire, the Kurds benefited from a certain degree of autonomy, but the establishment of the republic introduced policies of forced assimilation, prohibiting the use of the Kurdish language and repressing any expression of their national identity. According to numerous historians[1], these measures sidelined the Kurds, who make up some 15-20% of Turkey’s population of almost 15 million, and thereby sowed the seeds of a protracted conflict. This situation coincided with the Armenian “genocide” and the forced displacement of millions of people in the region.

The origins of the PKK

Founded in 1978 by Abdullah Öcalan, also known as “Apo”, the PKK initially aimed for the independence of a unified Kurdistan. The territory of this Kurdistan spanned Turkey, the USSR (there was once a Red Kurdistan in Nakhchivan), Iran, Syria and Iraq. Driven by Marxist-Leninist ideals, the group mounted an armed insurrection in 1984, featuring attacks on Turkish forces. As Turkey – Kurdish Conflict, Ethnicity, Borders, Britannica[2] reports, this campaign escalated an ethnic dispute into a civil war, costing more than 40,000 lives to this day. The PKK has set up bases in the mountains of southeastern Turkey, a territory called Rojava by the independentists, and in northern Iraq, capitalizing on the failings of a centralized state hostile to Kurdish demands.

In the 1990s, the conflict escalated, with the PKK receiving tacit support from Syria – home to Öcalan until 1998 – and Iraq, where the Kurds were also striving to consolidate their position. These dynamics had major regional repercussions, affecting Turkey’s relations with its neighbors. Syria, for its part, leveraged the PKK against Ankara, while Turkish military intervention in Iraqi Kurdistan exacerbated tensions with Baghdad (The Kurdish Issue in Turkey – CIAO[3]). This internationalization further complicated the resolution of the conflict, placing it in a broader geopolitical context. As we shall see before and after the fall of Sadam Hussein, the Kurdish question has been exploited on several occasions by countries in the region (first by Iran, then by Turkey, the USA and Israel), then later during the Syrian civil war and up to the present day.

Öcalan’s arrest: a historic turning point

Betrayed by the Al Assad regime in Syria, on February 15, 1999, Öcalan, the mythical and undisputed leader of the PKK, was apprehended in Nairobi, Kenya, in a joint operation by the Turkish secret services backed by the CIA. This arrest, reported in Devriş Çimen’s article in Jacobin[4], dealt a severe blow to the political-military movement. Sentenced to capital punishment, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 2002 following the abolition of capital punishment in Turkey, in response to pressure from the European Union. Locked up on the prison-island of Imrali, Öcalan came to be seen as a symbolic figure, leading the movement from his cell.

The arrest sparked a leadership crisis within the PKK, but did not halt its activities – in fact, quite the opposite. Öcalan, still influencing his followers, began an ideological transformation, discarding the idea of an independent state in favor of a “democratic confederation” within existing states[5]. This evolution towards culturalist autonomy redefined the PKK’s objectives, gearing it up for future negotiations while preserving its legitimacy among the Kurds.

The 2013 speech: Cessation of hostilities

On March 21, 2013, during the Newroz festival, Öcalan, via a message read by representatives, called on the PKK to cease hostilities[6]. He announced a unilateral ceasefire and ordered the militants to withdraw from Turkish territories, ushering in a peace process negotiated in secret with the Turkish government under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. This speech[7], intended to turn armed conflict into political dialogue, fell short of its objectives.

The appeal divided activists. For some, it provided an opportunity for peace, whilst others feared a capitulation to a state perceived as inflexible. The withdrawal of fighters to northern Iraq was partly completed, but persistent mistrust made implementation of the ceasefire all the more complicated.

Back then, Erdoğan welcomed the initiative, launching the “Solution Process”. Cultural reforms, such as Kurdish-language education, were envisaged, but progress was hampered by internal tensions and mutual accusations of bad faith. The process collapsed in 2015, reigniting the violence[8]. In the midst of Daesh’s advance into Syria and Iraq, Erdoğan embarked on a massive bombing campaign against the PKK. By lumping the Caliphate and the PKK together, the Turkish President outright dismisses the options for a peaceful settlement of the Kurdish question.

The February 27, 2025 speech: a new call for peace

On February 27, 2025, Öcalan issued a historic new statement, calling on the PKK to “lay down arms and transition to a peaceful political struggle”, even relinquishing autonomist demands. Shared by the DEM party, this announcement is based on “progress in Kurdish rights” and proposes a congress for the dissolution of the PKK[9]. The statement follows discussions with Ankara, authorized since December 2024 with pro-independence activists and left-wing political figures in Turkey.

This speech suggests a desire for definitive de-escalation, albeit with some doubts. Kurdish activists, wary of the broken promises of the past, are demanding reforms. The Turkish government seems keen to negotiate, but success will hinge on concessions such as recognition of Kurdish identity, particularly as Ankara has yet to make a public offer. Regionally, this initiative could stabilize southeast Turkey and influence the Kurds in both Iraq and Iran.

The impact of the conflict on neighboring countries and the connection with the Syrian crisis

Northern Iraq has served as a refuge for the PKK, provoking Turkish incursions and tensions with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which has been autonomous since 2005[10]. Öcalan’s appeal could reduce this friction, but the KRG’s ambitions for independence will continue to be a defining factor.

In Syria, the Kurds, via the PYD and YPG, have established autonomy in Rojava since 2011, fighting ISIS with US support[11]. The PYD’s acceptance of Öcalan’s proposal, announced on the afternoon of the February 27 speech, could signal a transition to negotiations with Damascus, but at the same time exposes the Kurds to risks vis-à-vis Turkey, which regards them as a threat. The decision could also strain relations with the United States, which supports the YPG but is opposed to the PKK.

In Iran, the Kurds, repressed by Teheran, are inspired by the PKK through groups such as PJAK[12]. The impact of Öcalan’s appeal remains limited there, although it could spur peaceful demands.

In Turkey, the conflict has polarized a society already divided by the aftermath of the failed putsch against Erdoğan. The 2025 speech, like that of 2013, offers a prospect of reconciliation, but previous failure underscores persistent challenges such as good faith or Ankara’s temptation to take its victory for granted without the need for concessions.

Erdoğan’s political and military victory: regional domination and military expansion

Since coming to power in 2002 with the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has consolidated his stranglehold on Turkey, elevating the country to a pivotal regional power and a virtual dictatorship with scant room for opposition. His re-election in 2023, despite an economic crisis and the after-effects of the February earthquakes, testified to his political resilience. Militarily, Erdoğan has bolstered the Turkish army’s capabilities and embarked on a massive deployment of troops abroad, estimated at 60,000 currently on overseas operations. These victories have heightened his domestic and regional prestige, as Ankara has forged alliances with numerous countries in the region, with Qatar at the top of the list.

Öcalan’s 2025 speech, provided it leads to a de-escalation with the PKK, could free up military resources hitherto mobilized in southeast Turkey and northern Iraq. This room for maneuver would reinforce Erdoğan’s ability to propel Turkish power beyond its borders, solidifying its dominance in the Near and Middle East against rivals such as Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Erdoğan’s foreign policy, melding pragmatism with neo-Ottoman ambitions, has repositioned Turkey as a key player. In Syria, operations such as “Olive Branch” (2018) and “Source of Peace” (2019) have weakened Kurdish forces and secured a buffer zone. In Libya, Turkish backing for the Government of National Accord (GAN) in 2020 repelled Khalifa Haftar’s forces, ensuring Ankara strategic maritime agreements[13]. These successes, combined with skilful diplomacy with Russia and the United States, have made Erdoğan an indispensable interlocutor, capable of challenging the region’s traditional powers.

Military expansion in Africa

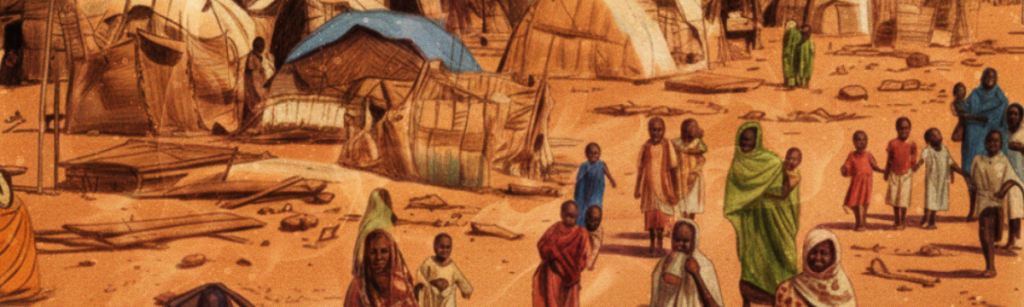

Armed with this regional foothold, Erdoğan’s Turkey is stepping up its involvement in Africa, where it is deploying forces and resources in a strategy combining soft power and military presence. In Libya, Turkey’s Al-Watiya base and drones have stabilized the GAN, giving Ankara access to oil resources and influence over the eastern Mediterranean. In Somalia, the Camp TURKSOM base, inaugurated in 2017, trains thousands of Somali soldiers and secures the Gulf of Aden, a strategic axis for world trade.

More recently, Turkey has signed military agreements with Chad and has reportedly begun deployment at bases abandoned by France (N’Djamena, Faya, Abéché) and is considering a presence in Sudan, where it is supporting factions in the civil war to counter Egyptian and French influence[14]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ankara is suspected of aiding the M23 rebels through the supply of arms.

While this African projection consolidates Erdoğan’s status as a global leader, it also entails a number of risks. Competition with France, China and Russia, particularly in the Sahel and East Africa, could lead to diplomatic tensions. Moreover, de-escalation with the PKK remains uncertain, and internal resistance could limit Turkey’s ability to maintain these foreign operations. Nevertheless, these military and political successes offer Erdoğan a unique opportunity to redraw Turkish influence from the Middle East to sub-Saharan Africa, despite an army stretched to the limit of its capabilities.

Should Ankara decide to play along, and should the response from PKK militants be massive, Öcalan’s speech, combined with the endorsement of the PYD, could prove a pivotal moment for reconciliation in Turkey, while Erdoğan’s victories bolster his regional dominance and pave the way for ambitious expansion in Africa. These dynamics embody Ankara’s desire to pacify its home front in order to better devote itself to its regional ambitions. Success depends on the political will of the players involved, amid a context where Kurds and Turkey are navigating between national aspirations and complex realities. As the Kurds seek their place and Erdoğan’s Turkey extends its influence, these events could redefine the future of the region.

[1] https://uca.edu/politicalscience/home/research-projects/dadm-project/middle-eastnorth-africapersian-gulf-region/turkeykurds-1922-present

[2] https://www.britannica.com/place/Turkey/The-Kurdish-conflict

[3] https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/iai/iai_99gam01.html

[4] https://jacobin.com/2025/02/abdullah-ocalan-turkey-erdogan-peace

[5] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17449057.2023.2275229

[6] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31998336

[7] https://blogs.mediapart.fr/le-courrier-turc/blog/280313/texte-complet-du-discours-dabdullah-oecalan

[8] https://www.americanprogress.org/article/state-turkish-kurdish-conflict

[9] https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/ocalan-dissolve-pkk-historic-statement

[10] https://www.cfr.org/timeline/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

[11] https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-between-turkey-and-armed-kurdish-groups

[12] https://ihd.org.tr/en/human-rightsthe-kurdish-issue-and-turkey

[13] https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/erdogan-in-egypt-strategic-implications-for-turkey-and-egypt

[14] https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/08/why-turkeys-erdogan-sings-same-tune-russias-putin-africa