Egypt’s War on Migrants

While authorities continue with their mass deportations to Sudan, a new asylum law could set a precedent in North Africa

Egypt is currently pressing ahead with the adoption of an asylum law. Although it is unclear whether it will actually be adopted, the situation of people on the move in Egypt is likely to remain disastrous in either scenario. The regime continues to respond to the arrival of Sudanese refugees with mass deportations to the war-torn country. The EU, meanwhile, is once again expanding its migration and military cooperation with Cairo and backs Egypt’s struggling economy with loans and grants, this time pursued to reduce irregular arrivals of people in Crete but also to keep el-Sisi’s regime in line for its role in Israel’s destruction of Gaza.

To the surprise of many observers, the Defence and National Security Committee in Egypt’s House of Representatives, the lower house of parliament, approved a draft asylum bill in late October 2024, followed by the parliament adopting the law only a few weeks later. The government had already drafted the controversial legislation back in 2023. The text itself, however, had remained undisclosed until October.

The draft law paves the way for transferring refugee status determination (RSD) from the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, to Egypt’s government ― with potentially far-reaching consequences. “It remains unclear how the law will affect asylum procedures in Egypt”, explains Mohamed Lotfy, Director of the Cairo-based human rights organization Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF). “Registration, RSD, and protection are to be transferred from UNHCR to a new governmental Permanent Committee for Refugee Affairs, but there is no clarity at all about how a transition period would look like or what exactly UNHCR’s role would be after the law is adopted”, he told the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Despite Egypt’s ratification of the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention in 1981, it is not the Egyptian state but only the Egypt branch of UNHCR that processes asylum applications in the country, grants people a refugee status, issues corresponding IDs, and ― at least on paper ― provides emergency assistance for refugees and asylum seekers. In a 1954 memorandum of understanding with the UNHCR, Egyptian authorities agreed to consider status IDs issued by UNHCR as proof of identity and to refrain from deporting people in the possession of those IDs. Nevertheless, people registered with UNHCR are denied access to education, the public health system and the formal labor market.

In other words: “The government is generally not concerned with the affairs and lives of refugees unless it involves security issues”, reads a paper by the migration researchers Prof. Dr. Gerda Heck and Elena Habersky of the American University in Cairo. If the government’s current draft law is ratified, this would certainly change.

Formalizing Deportation

The bill now grants refugees the right to education and access to the labor market for the very first time. However, “the law appears to prioritize security considerations over refugee protection, potentially undermining the right to asylum”, warns ECRF Director Lotfy. “The text contains broadly worded provisions concerning ‘acts that may affect national security or public order’. This vague language grants excessive discretion to the new committee responsible for determining refugee status, leaving the door open for arbitrary denials”, he explains.

For instance, the draft law allows authorities to detain asylum seekers until a decision on their asylum claim has been issued, and to deport them in the event of a rejection. It also introduces the misleading term of “voluntary return”, propagated by the EU and border regime advocates, into Egyptian law. By ratifying the bill, such “voluntary returns” would be permitted to a person’s “country of origin” or “habitual residence”. With those provisions, the law de jure formalizes the authorities’ detention and deportation practices against people on the move, which violate international law. The draft also prohibits refugees from joining trade unions and is apparently also aimed at criminalizing any kind of activism by refugees, as the Egyptian media outlet Mada Masr suggests.

The latter provisions are hardly surprising given the authorities’ paranoid fear of any form of self-organization or protest. In recent years, in particular Eritrean and Sudanese refugees and asylum seekers have repeatedly gathered in front of UNHCR’s office in Sixth of October City on the outskirts of Giza, protesting against the UN agency’s asylum recognition practices and demanding better living conditions. Egypt’s police violently cracked down on those sit-ins, while the intelligence service National Security Agency responded with intimidation, threats, and summons against Sudanese activists.

Meanwhile, assessments of the draft asylum law are anything but optimistic. Such a law would give many people residing irregularly in the country hope of finally getting out of their precarious situation. “On the other hand, hardly anyone has any illusion that an asylum law would seriously improve the living conditions of refugees”, says AUC professor Heck. Other voices are even more explicit. Such a law would end in “disaster”, since the state has neither the experience nor the capacity to carry out adequate asylum procedures, according to an NGO worker who wishes to remain anonymous. In a policy paper, ECRF calls for the draft to be revised, arguing that it must be comprehensively reviewed for its compatibility with the Geneva Convention.

A Trojan Horse?

It remains unclear whether the regime actually intends to actually turn the bill into law or merely follow Morocco’s lead and use the procedure as a means of exerting pressure on the EU, thereby turning Brussels’s obsession with the externalization of European borders onto North Africa into an asset in bilateral talks. The Moroccan government already began drafting such a law in 2014, but never had it ratified despite finalizing two drafts. In Tunisia, an asylum bill was drafted in 2017, but was likewise never submitted to parliament for a vote. In Turkey, on the other hand, an asylum law came into force in 2014 in the context of the government’s nationalist and geopolitical interest and the Turkey-EU deal that, according to critics, does not offer adequate refugee protection, but rather gradually eliminated UNHCR as a decision-making authority regarding the status of refugees.

In the Egyptian case, both paths are possible. The draft still has to be ratified by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi before coming into force. Prior to the introduction of national asylum procedures, the bill stipulates that a decree by the prime minister is necessary to define the administrative and operational framework of the committee. With these two pending steps, Egypt’s government has still leeway to delay the implementation of the law’s stipulations and demand quid pro quo from Europe.

The EU has been trying for years to persuade so called “transit states” in North Africa to adopt asylum laws and has supported the drafting processes of such legislation in Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt. Both UNHCR’s Egypt branch and the EU Asylum Agency EUAA have held workshops and training about asylum regulations and asylum management with Egyptian officials for years. Such laws would potentially allow EU states to deport those people to North Africa who have entered the EU irregularly and thereby externalize asylum procedures. The ratification of the bill in Egypt would set a precedent in North Africa. However, Egypt’s government is likely to avoid turning the country into a destination for deportations from the EU by adopting such law. Instead, by pushing the bill forward, Cairo appears to be attempting to outmanoeuvre UNHCR as the authority that decides who receives refugee status in Egypt.

Carrots and Sticks

Meanwhile, Egyptian police and military authorities continue to take rigorous action against Egypt-based migrants and newly arriving refugees. Egypt’s regime responds to the war between the Sudanese army and the RSF militia, which for a while was supplied with equipment by the EU to ramp up migration control in Sudan, with a carrot-and-stick approach. Shortly after the onset of the war in 2023, a coordinated smear campaign against refugees took hold in social media in Egypt, unanimously confirmed by multiple sources during talks in Cairo. Calls were made for mass deportations or the boycott of refugee-run businesses. One Egyptian MP claimed that country is experiencing an “invasion” of irregular migrants, arguing in line with last year’s smear campaign.

While there were already reports of some deportations to Sudan in mid-2023, Egypt’s government surprisingly launched a regularization campaign in September 2023, calling on people who had entered the country irregularly or those without a valid visa to regularize their stay. The initiative promised a legal status in return for a payment of 1,000 US dollars. The foreigners and visa authority in Abbaseyya in eastern Cairo has been packed ever since. Those seeking to regularize their presence sometimes have to wait up to six months for appointments. At the same time, authorities tightened visa and entry regulations for people from Sudan as well as Syria, and stepped up deportations to both countries.

Since the end of the one-year regularization campaign in June 2024, panic has spread across Egypt, similar to that caused by the latest wave of arrests and expulsions in 2023, explains an employee of an aid organization in Cairo. Police authorities had already initiated systematic raids, mass arrests, and deportations in 2023, particularly to Sudan. Yet, a kind of state of emergency has prevailed since mid-2024. Countless people on the move no longer dare to leave their home for fear of arrest, according to an aid worker who wishes to remain anonymous. Many of those arrested are released from detention after three weeks following a security check by the authorities. However, thousands of others have since been expelled to Sudan.

According to UNHCR figures, more than 5,000 people were deported to Sudan between April and September 2023, 3,000 in September alone. In November, yet another 1,600 were forcibly expelled to the war-torn country, including recognized refugees. A further 800 people were deported between January and March 2024, while press reports confirm another 700 deportations in June. The number of unreported cases is likely to be significantly higher, as refugees are now arrested by police or the military immediately after crossing the border in the south. Their phones are systematically confiscated, and they are later driven to the border in bus convoys after weeks in custody in police stations, the Shellal camp in Aswan run by the riot police unit Central Security Forces, or makeshift military facilities. Deaths during the dangerous irregular border crossings from Sudan to Egypt are also increasing.

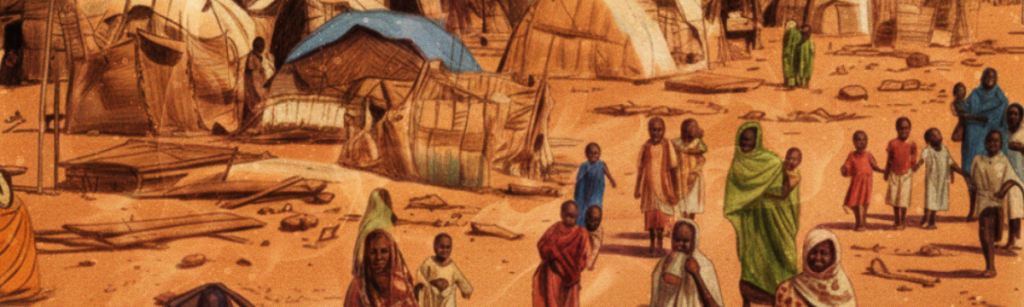

Europe’s Charm Offensive

For the EU and its member states, the war in Sudan remains the key reason for their intensified migration control and military cooperation with the el-Sisi regime. According to UN data, more than 11.6 million people have been displaced across Sudan since the onset of the war in 2023, at least 1.2 million of whom have fled to Egypt. The number of refugees and asylum seekers registered with UNHCR’s Egypt branch has more than doubled in only a year to 800,000 people, while the number of UN-registered Sudanese has almost tripled to 513,000 (as of October 2024). This year, the UN agency finalized RSD procedures for only 9,000 applicants, while 3,630 people were resettled from Egypt to a safe third country, compared to a mere 863 the previous year. Refugees from Sudan and other countries are essentially stuck in Egypt ― and the EU is doing everything possible to keep it that way.

As part of its migration containment policy disguised as humanitarian aid, the EU provided 25 million euro in 2023 in support funding for people in urgent need of protection and those fleeing Sudan ― while intensifying talks with Egypt on a comprehensive economic aid package. In March 2024, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen travelled to Cairo with the heads of government of Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Austria, and Belgium and signed a 7.4-billion-euro aid deal with Egypt, consisting of loans, grants, investments, and funds for border management projects worth 200 million. The deal once again links migration and development issues and aims at pave the way for closer cooperation between Egyptian authorities and EU agencies such as EUAA, Europol, or Frontex.

Brussels, Rome, and Athens seek to stabilize Egypt’s regime and the ailing Egyptian economy at all costs and create incentives for Cairo to integrate more comprehensively into Europe’s border control regime, which continues to systematically undermine international human rights and refugee law within and beyond Europe’s borders. In this sense, the EU currently pursues three main goals in Egypt: preventing Sudanese refugees from continuing their journey to Europe, closing the migration route between eastern Libya and the Greek island of Crete, as well as maintaining Egypt’s assistance in managing Palestinian refugees, which is by no means irrelevant to Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Against the backdrop of increasing irregular arrivals of Egyptians in the EU in recent years as well as Egypt’s role as a “transit” hub for those fleeing from war, prosecution, or famine, the EU Commission already launched a border management project for the Egyptian coast guard in 2022 worth 80 million euro. While these funds are partly earmarked to purchase patrol vessels, Brussels released another 20 million euro in June 2024 for armoured vehicles, drones, and radar equipment for the Egyptian military to be used on Egypt’s border with Libya.

Meanwhile, Israel’s war in Gaza, pursued in clear violation of international law and, according to countless Israeli officials, aimed at the systematic destruction of Gaza and the expulsion of the Palestinian population from the strip, is at the top of the EU’s mind when inking the billion-euro deal with Egypt in March. Egypt’s refusal to take in Palestinian refugees and thus further fuel the destruction and settlement plans of Israeli hardliners in Gaza is less an expression of the Egyptian state’s solidarity with Palestinians and more linked to security considerations on the part pf Egypt’s paranoid military and police apparatus as well as Cairo’s access to loans and grants from Western governments. Egypt’s collaboration with Israel and its allies in managing the border with Palestine remains key to any possible future scenario in Gaza. In the meantime, solidarity protests in Egypt continue to be dispersed and criminalized by the authorities.

Athens’s Quiet Anti-Migration Diplomacy

Israel’s systematic mass displacements across Palestine and the occupying army’s invasion of Lebanon are, much like the war in Sudan, grist for the mill of forced migration in the region, and thereby also for the EU’s border externalization policy in the eastern Mediterranean. In light of the rising number of people fleeing Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine in boats bound for Cyprus, Brussels also inked a migration deal with Beirut in 2024. Since 2023, Lebanese authorities have carried out deportations to Syria and intercepted boats carrying people to Cyprus much more relentlessly than before. For its part, the Cypriot coast guard is also intercepting people setting sail in Lebanon and returning them to the crisis-ridden country in clear violation of international refugee law, effectively following the Greek model.

Today, Athens’s rigorous approach regarding refugees and people on the move is notorious far beyond Europe’s borders and ranges from illegal refoulement practices and the criminalization of people on the move to a camp policy on Greek islands unparalleled across Europe. “Greece has a history of pushbacks and summary expulsions without the assessment of third-country nationals’ human rights protection needs, on land and at sea”, migration researcher Maria Paraskeva wrote in a 2023 report for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Athens Office. Pushbacks follow a decade-long pattern and are carried out routinely and systematically.

Meanwhile, today’s main concern of border regime stakeholders in Greece is the increasingly busy migration route between Tobruk in eastern Libya and southern Greece. Crete-bound boats carrying people who have entered Libya via Egypt have repeatedly capsized here too ― most recently in October 2024. Despite these developments, Greek authorities refrain from raising attention to the increasing flows in Crete in a systematic way and from presenting a concrete plan to manage the situation, Pareskeva tells the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. “However, the recent arrival of 200 people in Crete in October 2024 and the arrival of 1,500 people on the small island of Gavdos, south of Crete, in April 2024 was highlighted by the Greek press at least briefly, and Greek authorities were forced to comment on it. Yet, the government is trying to appear as if the state has the situation under complete control, stressing that the state has successfully stemmed immigration flows to Greece.”

In light of this government narrative, Greece’s conservative Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis travelled to Cairo with the EU Commission President in March. “The Greek government is afraid that more people from Egypt could enter Europe on the Crete route in the future”, says Pareskeva. It is therefore no surprise that the Greek coast guard has already refused to disembark people on the move rescued from distress at sea by merchant vessels on the southern route in two cases confirmed by Alarmphone and diverted them instead to Port Said in Egypt. So far, however, this policy has not been systematic on this route, the SAR NGO said in a report.

“Containing Undesired Mobilities”

Egypt’s regime had already successfully exploited migration movements in 2016 to gain leeway in negotiations with external lenders, but also to rehabilitate the regime on the international stage after the military’s bloody 2013 coup. In late 2016, Egyptian authorities effectively closed down maritime borders after a fishing trawler capsized off the Mediterranean coast, thus allowing the regime to portray itself as a reliable partner in migration control. Migration-related developments in the region in recent years have now given el-Sisi’s regime yet another opportunity to trade stronger migration control for loans, grants, or investments.

The policy of summary deportations to neighbouring Sudan, following the Algerian model, is an indication that the border regime logic, propagated by the EU and its proxies, has now fully taken root in the Egyptian administration. Meanwhile, the draft asylum law is yet to be ratified, but would, if adopted, constitute another brick in the EU’s externalized border regime in North Africa. This and other steps clearly show how the EU’s holistically driven approach towards migration and development in countries such as Egypt reshapes the “political, humanitarian, as well as migratory landscapes” of a country, and is aimed at “integrating, and containing ‘undesired mobilities’” outside of the EU, according to AUC researchers Heck and Habersky.

The “combat against root causes of migration” pursued by European liberals in countries like Egypt is nothing more than a perverted euphemism for a neocolonial policy that attempts to delude the public into believing that charity schemes in the Global South disguised as “development projects” can stop migration. The urgently needed debate on the structural economic and trade imbalances between countries of the Global North and South is thereby further undermined by the dominance of this distorted development discourse, while international human rights and refugee law is eroding on an even faster pace. It is therefore no surprise that the EU Commission and the governments in Berlin, Rome, or Athens do not care when being criticized for their “cash-for-migration-control approach” or when being held responsible for their “complicity” in human rights abuses by human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch in the context of externalizing border regimes to North Africa.